Dear Friends,

Oh yes, while the pandemic gave me and so many others hours at home to research and write, doesn’t it feel that getting out into the world makes time evaporate? I’m not complaining, not my style—just yesterday I was talking to a neighbor here in New York about the exquisite beauty of the ice coated trees and shrubs glistening under blue skies and he said, why so optimistic all of the time, all I see is the likelihood that I will slip and fall and that will be that.

I’m glass half full for sure, but the empty half is what keeps me seeking and studying solace. And I’m supercharged when my own peace of mind is challenged. On that note, this week, I’d like to share with you a recent adventure in what I’ll call matters of the heart.

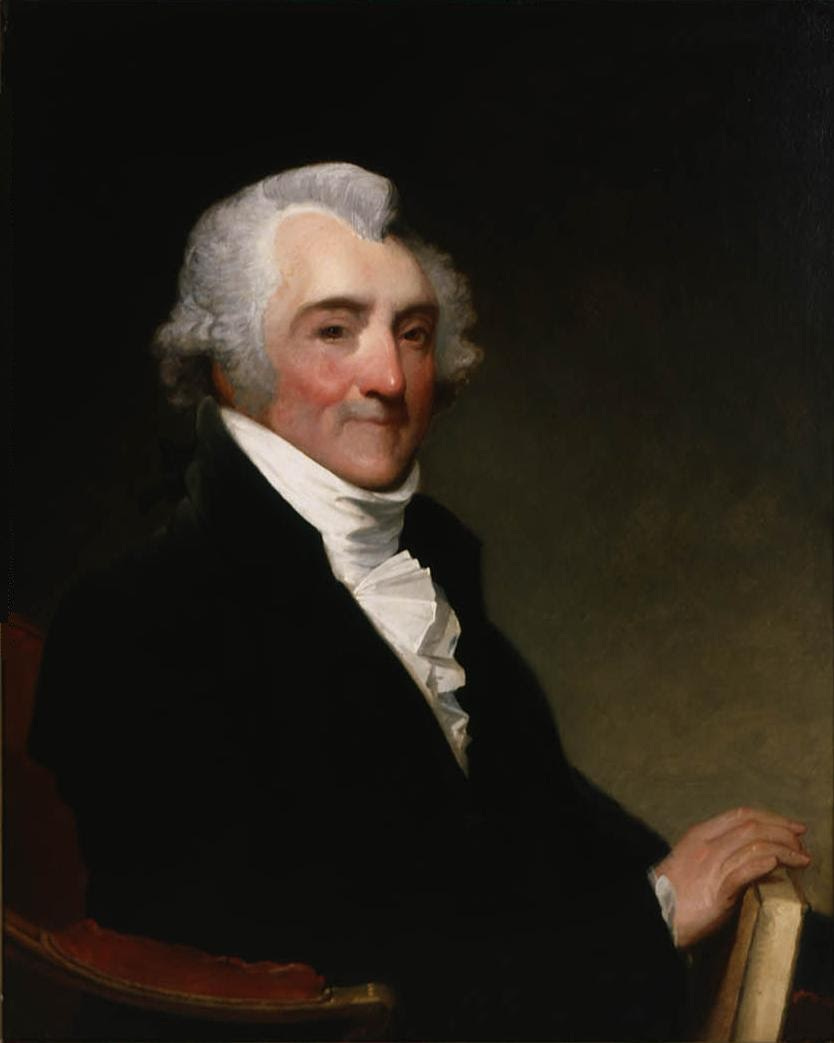

I love when my mind conjures an image or thoughts from way back, where is all of that stored so that it pops up right when I need it? Meet Dr. John Collins Warren (1778-1856), painted by Gilbert Stuart in Boston in 1812, just after Warren was appointed professor of anatomy and surgery at Harvard Medical School. More on him in a minute, but me first. I conjured him to help me with matters of the heart, on which he was an early explorer. I mean the actual heart, the aorta that keeps us moving, breathing, thinking, and feeling. By now, we are all sick and tired of me writing about my broken arm, and yet it has provided endless fodder for thought. The heart part goes like this: after I tripped on that curb at a rest stop in Pennsylvania back on October 3 and drove myself the two hours home, I was so flushed with adrenaline and random endorphins as a reaction to physical trauma, that I fainted when I relaxed. Walked in the door, sat down, amazed that I had made it, and then stood up and fell down. Now I know that’s called orthostatic hypotension, basically low blood pressure that caused me to go limp. I promised myself, long ago surely after listening to older folks talk about ailments, that I would never talk about such things, more than that, that I would never have such things about which to talk. That night in the ER, the orthopedic doctor said you broke your arm, stay still, sleep as much as you can, you’re good to go. That’s my girl. And as I got up to leave, the cardiac doctor said not so fast. And so ensued four months of doctor visits for a heart, my heart, that was just fine. Checks and checks and checks, with all sorts of monitors and fancy equipment, all waiting for the aptly named Stress Test, a test that causes stress. The irony is that I couldn’t take the stress test until my arm was completely healed and I’d had weeks of physical therapy, lest I fall off the treadmill in a front-open gown. How undignified. I passed the test last week, a morning of severe anxiety balanced with extraordinary well-being, the very essence of solace. The balance. I hadn’t had so many ultrasound images since I had my second daughter in 1997, so cool to see my heart beating on the screen. The doctor said “treadmill next” and I said ok. She said, “we’ll take it easy, please tell us when you get tired, it will probably be less than 10 minutes.” I said “I won’t get tired. I run, really run.” Sure enough, my heart is so healthy that they had to jack up the incline and the pace to even get my heart rate to the desired point. She said “now hold it there, keep running for 3 minutes and then dive to the table before it drops.” Stop, drop, don’t roll. All good.

Truly ridiculous, but walking out onto the street, I realized that I had been stressed for months, waiting for the clean bill of health. Now I have it, perhaps lots to say about that, but more importantly, young Dr. Warren popped into my mind. The Doogie Howser of early 19th century Boston, except that John Warren made medical history. Just look at his portrait. When he sat for Stuart in 1812, he was 34 years old, a distinguished surgeon with an office on Park Street, on the Boston Commons (now a law office and a Dunkin Donuts). The heart in the drawing he holds is unwell, clogged arteries, state of the art in 1812, remarkably an image much clearer than the ones I saw on the screen last week of my own heart.. Warren knew Stuart well, he was the family physician, and Stuart—who by this time could punt a picture—took extraordinary care to convey Warren’s genius. He got hold of the image from his studio assistant, the artist John Penniman (on all of this I am, once again completely indebted to Ellen Miles, who did such wonderful research on this portrait long ago and probably still thinks about it, as do I). Here’s another thing I think: I’m looking closely at Stuart’s predominantly red composition and want to connect it to John Singer Sargent’s 1881 portrait of Dr. Samuel Jean de Pozzi, the esteemed French gynecologist.

Maybe just a wise-crack comparison—oh all of the blood these gentlemen saw in their respective professions—reminds me to someday research how Sargent might have seen this portrait in the Warren family home in Boston once upon a time.

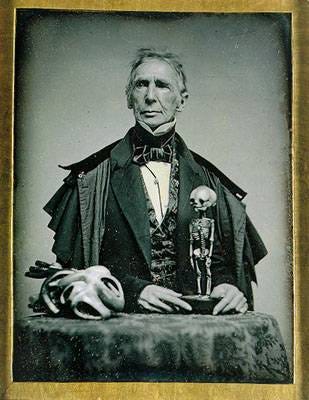

For now, though, as I still think about all of the contraptions that went into my own non-diagnosis, I looked up Dr. Warren’s groundbreaking book, Cases of Organic Diseases of the Heart, with Dissections (Boston, 1809), printed from lectures read before the Counsellors of the Massachusetts Medical Society. Do click the link, you’ll get the entire book of captivating case studies of ailing people, all of whom died and then went under Warren’s knife for study. Thomas Appleton, age 38, had difficulty breathing, Mrs. T, age 56, “of excessively corpulent habit” lacked energy; Mr. John Jackson, age 52, experienced palpitations and paroxysms (aka spasms); Captain Job Jackson, age 45, reported “superadded dizziness”; A. B., an enslaved worker had chest pains; Mrs. McClench, a washer-woman, was severely fatigued; and Colonel William Scollay, age 52, “of plethoric habit of body” suffered from dropsy (meaning he retained water and had swelling). Levi Brown, a 48 year old cabinet maker, had trouble breathing, but decided he was a hypochondriac since he was of “an active mind and had read medical books.” Mr. Brown was “of very robust frame of body and had been accustomed to a free use of ardent spirits and opium.” And finally, the late Governor of the Commonwealth (not named by Warren in his lectures, but surely James Sullivan, who died on December 10, 1808, having served 18 months in office), here’s a look at him, florid face and all, also by Gilbert Stuart.

The governor suffered awfully, no sleep, no appetite, constant pain, dizziness, edema, all of it. Yet, “the state legislature convened, and the call of business roused, like magic, the vigor in his mind; and the symptoms of the disease almost disappeared… As soon as the legislature adjourned, he declared that his work was finished.”

Warren himself worked on, perhaps knowing that walking and loving what we do keeps us alive. He founded Mass General Hospital in 1821 and notably, at age 68, performed the first surgery under the influence of anesthesia, known then as ether. That is a sort of solace too.

Take a Walk

Dr. Warren again, reports the case of “a lady from the country, of robust habit, whose age is about thirty-five years,” a recent widow left with “a number of small children” and “small means.” In her suffering, she said that “the exercise of walking slowly, in pleasant weather, although it increased the palpitations at the moment, is followed with relief from the distressing feelings, which are increased when she sits for a long time.”

And onward

More next week,

Until then, keep walking and looking, slowly and with curiosity and courage,

Carrie

Share this post